According to the European Commission, biostimulants are “Substances or micro-organisms whose function when applied to plants or the rhizosphere is to stimulate natural processes to enhance/benefit nutrient uptake, nutrient efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, and crop quality.”

The reason I need to start an article on biostimulants with a dry definition is because they do not belong to one specific category of ‘thing’ and can be derived from a range of sources, including;

| Extracts | Microbials | Chemicals |

| Plant | Fungi | Phosphites |

| Algal | Bacteria | Silicates |

| Fungal | Animals (nematodes) | Synthetic organic chemicals |

| Mineral | Protists | |

| Animal |

Each specific form of biostimulant will be covered in at least one of the upcoming blog posts, so keep coming back!

Despite coming from a wide range of sources, there are certain key features to look for when choosing a product to distribute or apply to your crops.

Specific modes of action (MoA)

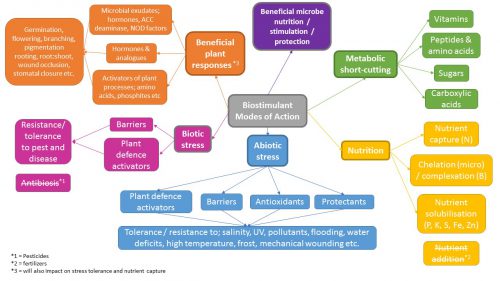

The product you choose needs to solve a real problem for your customers. Too many times you will see marketing material for biostimulants where the only discernible MoA is ‘increases plant growth’. That is not good enough in the current climate. The more detail the better, and even better if this can be linked to scientific literature to back up the claims. Below are some extremely broad areas of biostimulant actions for products already on the market. You should demand far more information than a simple sentence or two on the subject of ‘mode of action’ and beware of products that claim to have every MoA under the sun!

Unique selling points

Avoid generic products that are already well-established in the market – otherwise be prepared for a tough sell. That is unless you have obtained an especially generous deal with your supplier that will allow you to undercut your competitors.

Quantifiable active ingredients

For some biostimulants the active ingredient may be accounted for down to the specific chemical compound, while for others it may simply be ‘contains plant extracts’. So you will need to determine how much information you require.

The supplier may be unwilling to divulge active ingredients. I believe that this stems from four potential reasons:

- They want to protect their intellectual property. This is understandable, but it can make products look like magic potions that just need ‘trusting’.

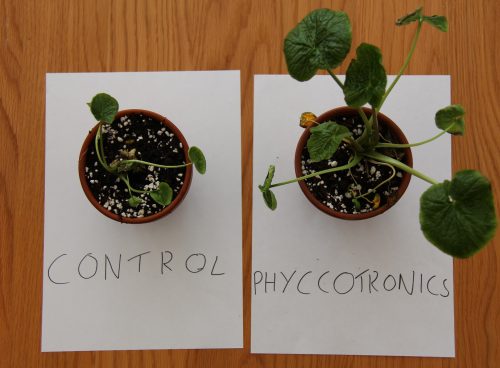

- They think it will add to the products kudos; whereby they replace ‘contains seaweed extract’ with something like ‘PHYCCOTRONICS INSIDE’ because it sounds fancier.

- They aren’t the primary manufacturer and so want to hide that fact from the customer (who might go direct to the real producer).

- They do not have the legal right to sell the product on under their own name from the original supplier.

It is always best practice to analyse samples yourself for their composition, rather than rely on data from the supplier. While you might not have a fully equipped laboratory to hand, there are plenty of analytical laboratories offering their services for modest fees. This was not always the case, especially when it came to determining the species and concentration of microbial products. However, the price of these analyses has dropped dramatically in the last few years (going from tens of thousands of pounds to a few hundred at most).

I would also advise you to not tell a laboratory what you expect them to find. I have seen reports on a microbial biostimulant where the customer has informed the lab of the species and concentrations they expected, and low and behold, the lab found all the species (no more, no less) and at the exact concentrations stated! I always use anonymous codes for samples, and through this technique have come to trust specific laboratories for the analysis of fertilizer and biostimulants.

Of course, you could choose to distribute a biostimulant with no clear active ingredient based on impressive trial results and marketing material, but who will buy it? In the UK, farmers and growers now critique all their inputs – this is down to the extensive supply chain audits required to satisfy supermarkets. Would they risk putting a product on their crop if they did not know what was in it?

Lack of “unwanteds”

Will sodium levels, heavy metals, allergens, or microbial contaminants be an issue for your intended use? For some customers, colour or odour may even be the critical issue.

Allergens could feasibly be an issue when working with by-products from the seafood and nut processing industries, while microbial contaminants could occur in both extract and microbial products if preserved and stabilized incorrectly. It is therefore advisable to send samples to a third-party lab to confirm the levels of any compounds/microorganisms that you may be concerned about.

You may also want to check that the biostimulant has not been ‘spiked’. By this I mean adding plant nutrients to ensure that the crops respond in an obviously positive way. Yes, applying a biostimulant with 3% nitrogen will produce lovely green lawns, but is it the biostimulant or the fertilizer producing this effect? Spiking may be fine for you if the fertilizer component is disclosed, but don’t be sold a ‘pig in a poke’! In all cases, you will want to avoid buying any product combined with a pesticide which may be effective, but is going to run afoul of many regulations and laws.

Formulations that work for you

This could be clearly a topic in its own right, but to summarize, you will need to check that the product is;

- Tank mix compatible with co-applied agrochemicals and biologicals.

- Fully soluble/miscible, or if an emulsion/suspension that it doesn’t block filters.

- The correct concentration; too high and users struggle to handle it accurately and if too weak you end up selling mostly water.

- Contains the correct adjuvants to maximise action; i.e. surfactants, wetters, antifoaming agents.

- Preserved in a way that maximises shelf life, that doesn’t impact the product’s performance, that is organically certifiable (if an issue), and is safe for the user.

Reliable independent trial results

This is one of the trickiest features of biostimulants to try and navigate. It essentially comes down to ‘do you trust the authors of the trial reports?’ Field trials conducted by the company selling the product (or farmers receiving the product free of charge) are fine as an indicator of how to use the product, but don’t hold much rigour. Conversely, if the trial was run by an organisation or institute you know to be of the highest integrity and with no declared financial interest then this is clearly valuable. Often the best trials are conducted by industry bodies, and are what I term ‘beauty pageants’ comparing a range of products from different suppliers.

Then there is the question of how much information do you require to satisfy yourself that the product works? Do you need a simple statement on increase in yield? Would the picture below suffice? Or do you want to see a thorough report written by a scientist who has conducted multiple trials over several years? In reality, you often want enough information to convince you to go to the effort of trialling the product yourself.

For early adopters of technology, trial data may not be available yet. Therefore analysing the product yourself may be essential, and get you a lead on other potential users. Such ‘co-development’ can also be used as leverage in negotiations on exclusivity.

Distributors analysing products themselves is not just good due diligence, it also allows your team to become experts on the product. Potentially you will reach the point where you know more about the product than the producer. In fact, the producer may not even know the exact details of what is in their natural extract, or how it works, therefore you could access key markets they cannot. Obtaining this information yourself also ensures that the producer cannot transfer this intellectual property over to other distributors who may be your competitors.

Primary manufacturers

As with sourcing any raw material, it is usually best to identify the primary manufacturer. If not, you could be paying far too high a price. However, this might not always be possible, due to exclusive distribution agreements already in place. It might also be better to use a trader when you want limited quantities, or they are offering generous credit terms or additional services. If this is the case, it should still be possible for you to be informed who is the original manufacturer. Therefore, be sceptical of companies claiming to be primary producers if site visits are off the table and/or the supplier doesn’t have a site where the product could feasibly be manufactured.

Strategic partnerships

Seek suppliers who will support your business by innovating and testing their products and telling you first about their findings. You should also find a supplier who will minimise competitors challenging your business with the same product. The obvious way to do this is to seek exclusivity agreements or rebate schemes to create barriers to entry for new competitors.

You should always try and avoid working with manufacturers who are, or would be willing, to sell direct to your customers.

Products that are not overly-burdened by regulatory restrictions in your country

Products containing animal by-products can face additional regulations or even be banned in certain countries. So it is best to check the lay of the land before entering new countries with these products.

In some countries, products may have to meet minimum standards for the active ingredient concentration to achieve a registration. This is especially the case in Spain and many South American countries.

If organic certification is an issue for a significant proportion of your customers, ensure that any certification is valid in your country. If you will be processing the certification application yourself, seek assurances from the supplier that the formulation is organically certifiable per the regulations in your country. This is especially important for preservatives used in natural extracts or to stabilize microorganisms.

Compliant safety documents

Substances and mixtures must now be classified, packaged and labelled (CLP) in compliance with the UN Globally Harmonized System (GHS) as enacted by the CLP Regulations within the EU.

Compliant Safety Data Sheets need to be produced and supplied to the downstream customer at or before the first order is received and again in case of significant revision. Despite being ‘globally harmonized’, some variations in requirements exist between the different global trading blocks, so be aware of this when importing biostimulants. The (supply and transport) hazard labels attached to the product container and to the outermost layer of packaging need to comply with current and relevant legislation.

Not only are GHS and CLP legal requirements, but the compliance of a supplier also gives you confidence that you aren’t working with cowboys. A supplier cannot refuse to supply a SDS to a downstream customer, so be wary if they try.

If you have any concerns or questions about any of the issues in this blog, please get in contact and I will be happy to advise or clarify further.

-500-width.jpg)